Raul Magni-Berton, Professeur de Science Politique à Sciences Po Grenoble et au laboratoire Pacte, Simon Varaine, doctorante au laboratoire Pacte, et Abel François, Professeur d’Economie à l’Université de Lille et au LEM

In March 2019, the French polling firm IFOP showed that 39 percent of respondents believe that their country is unreformable and a revolution is needed to improve the condition of the country. While this huge percentage could be partly due to a specific situation of this country, revolutionary attitudes have regularly increased over the last three decades in Western Europe. According to the European Value Survey, in 1990 an average of 4.5 percent of survey respondents desired a revolution. In 2008, they were eight percent. Moreover, this increase in revolutionary attitudes is documented in all Western European countries but Sweden.

This trend is particularly puzzling in established democracies, because democratic regimes are known to provide citizens with institutional and legal ways to change the rules and the rulers. As Karl Popper famously argued: “under a democracy the government can be got rid of without bloodshed; under a tyranny it cannot”. Discontent people can join or create a political party, are free to express their opinions and to punish their governments. They do not need any revolution to change the rulers or the rules of the game.

Our recently published article in Political Studies comes back to three basic arguments supporting the alleged peaceful virtue of democracies. We show these arguments are correct, but contemporary European democracies are less performant to comply with these democratic requirements.

The first peaceful property is the majority rule. People are always discontent when they are ruled by an unwanted government. Some of them are so discontent that they desire to overthrow the rules of the game with revolutionary actions. The only way to reduce the number of discontent citizens is to minimize the number of political losers. Majority rule does it.

The second peaceful property is the alternation in power. Being a political loser could be not enough to develop revolutionary attitudes. Citizens support a revolution when they cannot expect their preferred party to rule in a legal way. This is Popper’s argument: as long as people hope to win the next election, they will not support a revolution.

The last peaceful property is the division of power. Power-sharing institutions guarantee that the political losers do not lose too much. Since depriving groups of power fuels revolutionary attitudes, sharing powers reduces this deprivation and, therefore, the likelihood of developing revolutionary attitudes.

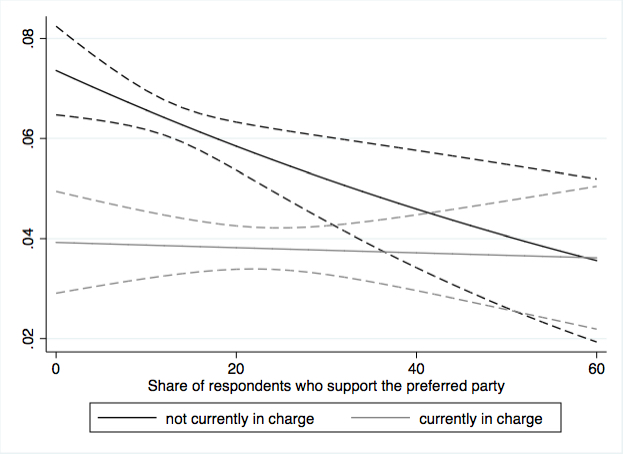

Through an analysis that includes fifteen European countries, three periods from 1990 to 2008 and almost 40.000 surveyed individuals, we demonstrate these three classical arguments are true and reinforce each other. In particular, figure 1 shows that the preference for revolution is more likely when respondents are close to a party that lose the elections. Interestingly, individuals who declare not to be appealed by any political party are particularly revolutionary. Figure 2, shows that, contrary to incumbents’ supporters, the opposition parties’ supporters are all the more inclined to wish for a revolution as their party is unlikely to win the next election.

Fig. 1 Probability of desiring revolution according to partisan preferences

Fig. 2 Probability of desiring a revolution according to the probability to win the next election

In short, the most peaceful democracies have a proportional electoral system and a highly fractionalized parliament; they practice minority governments that require other parties’ support to work effectively; and they experience alternation in power. The best example of this democratic institutional profile is Denmark, where revolutionary attitudes are the lowest in Europe.

So, can we explain the increase in revolutionary attitudes by a decline in peaceful properties of democratic processes? Partly yes. On the one hand, no facts enable us to affirm that division of powers is declining in European democracies. On the other hand we observe the supporters of political parties having no chance to win in the future are slightly more numerous, according to our measures. However, it is not enough to explain the huge increase in revolutionary attitudes. Actually, the main problem is that the winners are less numerous than 30 years ago, simply because the number of people who vote for parties excluded from governmental coalitions increases.

Our general results are, of course, differently applicable to each country. For instance, in UK and Germany, the number of winners did not really decline. In the meantime, the share of voters for parties having never ruled and having few chances to take part in a future governmental coalition increased. In France, the number of winners hugely decreased due to the electoral system. The ruling majority used to be elected by around 30 percent of the registered voters in the nineties, in 2017 it was only by 15 percent. It can explain the recent yellow vest revolt and enables us to predict similar events in countries with similar propertie

Ce texte est issu d’un article publié dans la revue Political Studies.