Guillaume Roux, Pacte-CNRS avec Aurélien Lignereux, Sciences Po Grenoble, CERDAP2

Neighbourhood stories. For a long-term survey of community–police relations in the French banlieues

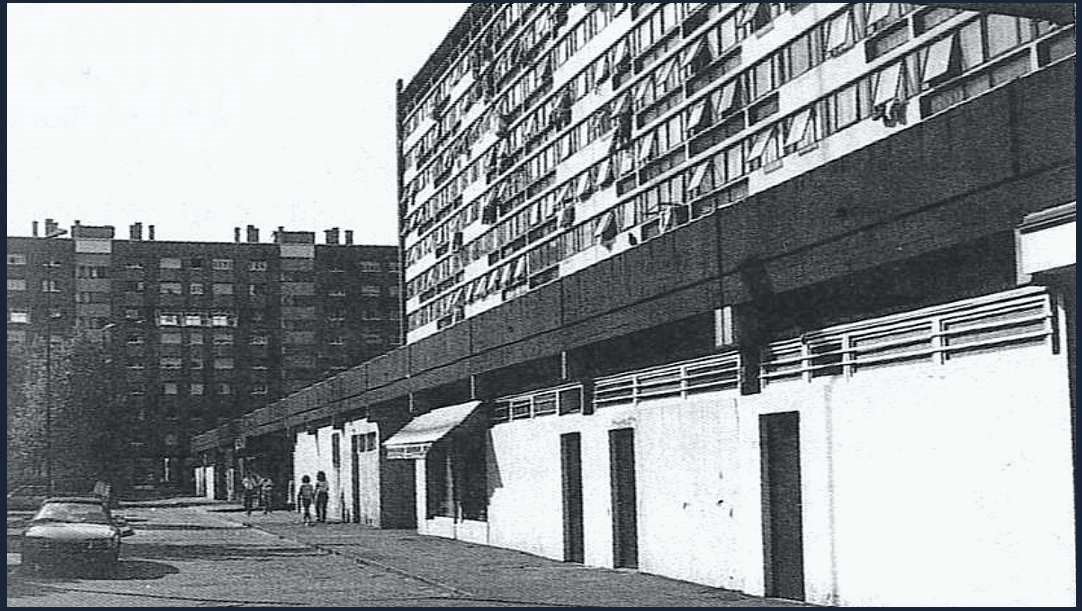

In March 2019, Mistral, a so-called sensitive neighbourhood of Grenoble, experienced several consecutive nights of rioting. These followed on from the deaths on the 2 March of two youngsters on a scooter in the course of a hot pursuit by the police, more specifically the crime squad. One of the youngsters lived in the neighbourhood and the other was known there. The police action was fiercely criticized, primarily in Mistral but in other banlieues of Grenoble, too.

By a knock-on effect, some of those areas became the scenes of confrontation between young people and the police. Many in Mistral thought the pursuit by crime squad officers, in circumstances liable to endanger the youngsters’ lives, was wrongful and even shocking. In the neighbourhood, it raised various questions about compliance with formal or informal rules of policing. Moreover, as often happens with affairs of this kind, the official police version of events, put out by the media or the authorities, was challenged or at least prompted “calls for the truth” and clarifications. Graffiti appeared on walls in the neighbourhood demanding justice, calling for the officers to be transferred away from the area, or more radically dismissing the institution.

Although a reaction of the kind seems natural – the Mistral incident is reminiscent of other events, beginning with the comparison commonly made with the deaths of Zyed and Bouna at Clichy-sous-Bois –, there is nothing self-evident about it. First, unlike other so-called sensitive neighbourhoods of the metropolitan area, Mistral had not experienced full-blown rioting before. As in other French banlieues – and perhaps more so – some residents want a police presence to counter the drug dealing that features regularly in the local media.

A survey in recent years showed that police action in Mistral, although much criticized for its ways and means, was thought legitimate – which is far less true in other parts of the city (again judging from our research). Unlike at La Villeneuve, for example, we have not found any trace of a negative collective memory of the police, built up over the course of time, as an “enemy” of the neighbourhood and its residents (which may be passed down between generations). Accordingly, beyond superficial likenesses, the situations in the French banlieues in terms of their relations with the police are highly contrasted. Field surveys alone can identify those contrasts.

Police action as viewed and recollected by residents

These local situations can largely be understood from the past record of police-community relations. In several banlieues of Grenoble, specialized police forces have intervened for some time now (under the various arrangements experimented in recent decades: Structure Légère d’Intervention et de Contrôle, équipe de CRS, Brigade Spécialisée de Terrain, etc.). They are not spontaneously perceived as unwanted. Depending on the cases and the groups in question, the opposite may even be true, with residents in some areas deploring the lack of police presence and calling for neighbourhood foot patrols. However, in several of these areas, law enforcement services have become associated over time with practices or interventions that have left a negative impression and become a focus for community-police antagonism.

Such conflict relates to a greater or lesser degree, depending on cases (individuals or areas) to the heavy-handedness of “police raids”, to the forms patrolling has taken by way of surveillance of an area and a “suspect community”, and to discriminatory police stops based on physical appearance (these various complaints may be combined or separate).

From this perspective, police targeting of certain neighbourhoods gives rise to what may be a lasting rejection. The reasons for this may be practical, with some residents evoking heavy-handedness and sometimes a fear of the police and their interventions (for themselves or their children). But there are symbolic reasons, too. Whether deliberately or not, the police send out signals that concern both policing intentions with respect to a neighbourhood or its inhabitants and their status – that of a group that is viewed as respectable or as more troublesome (and which may feel despised). Police action may therefore reinforce, on the ground, the stigmatization that affects residents of the French banlieues and especially members of ethnic/racialized minorities. Without bringing things down to this single dimension, though, our research has shown that the interpretation of police targeting by residents of what are labelled sensitive districts – and especially the feeling of being targeted as a member of a “suspect group” – depended largely on the residents being identified as white or non-white.

In Mistral, the police targeting mechanism (assignment of a specialized squad, increased number of interventions, etc.) has been comparatively recent. It follows the neighbourhood being categorized along with a few others in Grenoble as a Priority Security Area in 2013 (although repercussions on the policing of the area were not immediate). Although the principle of police targeting was not massively challenged there until then, will the events of March 2019 change the deal? There is now a deficit to be made up, which the police may or may not decide to take into account. This applies both to the form of police interventions and to the attention paid to calls from actors in the neighbourhood or from residents who speak out publicly (and sometimes complain they are ignored). For all the others, only the field survey can account for the diversity of complaints and provide an understanding not just of how police actions pose concrete problems (when the residents feel endangered) but again of the way police targeting is symbolically interpreted.

The MéMim projet

The MéMim research project brings together specialists from various disciplines (historians, political scientists, geographers, etc.). It seeks to understand how antagonism builds between communities and the police within different working-class neighbourhoods – and how steps may be taken to alleviate it. The project begins with the observation, as the outcome of the field survey, that such strife is invariably part of specific, historically contingent, local configurations on the neighbourhood scale. It seeks insight into how local patterns are gradually built up. This involves examining neighbourhood targeting – dependent both on police decision-making but also local or national action by other public actors –, the different events, incidents or tragedies that leave a lasting mark, and the “reactions” of the neighbourhood residents to the extent that they can be understood as part of a history of the present time, extending back to the 1970s.

Even if such a set of issues runs up against the limits of historical records and the degree to which they can be disclosed, comparison among the neighbourhoods of one and the same metropolitan area seems to us to be heuristic as of present. Findings at this local level thus enlighten certain observations from national or international studies (opinion polls, etc.) about community-police relations (concerning for example the correlation between distrust in the police on the one hand and the frequencies of “police raids” in a neighbourhood on the other). They can also identify “blind spots” in the literature, especially in literature on criminology, that are not principally about documenting the existence of local contentions between the community and police, and start up a dialogue with that literature. From the stand point of political science, this work resonates with the relatively recent observation that the role of the police with regard to the major issues of the discipline has been underestimated. This holds in particular for the way in which residents from working-class neighbourhoods (or an underclass) and/or ethnic minorities see their relation with public action and society (which fits in with work on policy feedback, citizenship, racialization or the processes of collective categorization/identification). In terms of historiography, the project is part of a strand that, having taken an interest in the knowledge, know-how, cultures and practices of law-enforcement actors, is now in a position to account for the reshaping of relations between police and communities and the interactions at work on the ground. For geography, it can be asked how police action contributes to the salience of the “neighbourhood” as a physical boundary but also a symbolic boundary, with the principle of ranking and social division.

Beyond the dividing lines and partitions between the disciplines, the project is part of an endeavour to re-evaluate the role of the police in the formation of the main socio-political divides and antagonisms that mark social life, and in particular the racialization process. It also ties in with a body of work on the production of the norm and deviation from it – and more specifically of groups that are thought to be “at risk” – on the basis of practices and mechanisms of public action on a local scale. Beginning with the observation that the police have the power to shape reality as the stuff on which governments reason (Paolo Napoli), it is possible to re-evaluate the role of the police and politicians (or government in Foucauld’s sense). How do they come up with the principles behind the ordering and division of the social world – this in relation with what are in part contingent local practices and arrangements?