Simon Varaine, Docteur en science politique, Sciences Po Grenoble, Pacte ; Ismaël Benslimane, Docteur en philosophie, Université Grenoble Alpes, IPhig ; Paolo Crosetto, Directeur de recherche en économie, Université Grenoble Alpes, GAEL ; Raul Magni-Berton, Professeur de sciences politiques, Sciences Po Grenoble, Pacte

Parochial altruism designates the individual motivation to costly engage in violence against other groups for the benefit of their group. Such type of behavior is typically encountered in inter-group conflicts and wars; one archetypal example being terrorism. Terrorists inflict costs to other groups and to themselves for the (expected) benefit of their own group. Crucially, in contrast with other forms of inter-group conflict, evidence indicates that terrorists generally have altruistic motives: most of them behave by their own volition and do not benefit personally from their involvement

There is a large literature on the reasons why individuals engage in parochial altruism. In our new paper published in Political Behavior, we take a step aside and ask: why parochial altruists target specific groups instead of others? In different times and places, terrorists have engaged in violence against very different groups. Fifty years ago, European terrorists attacked the big capitalist firms and government forces. Today, a growing number of terrorist active in Europe target immigrants, ethnic minorities and economically weak individuals. Why do the targets of parochial altruism change depending on the context?

In our paper we distinguish two types of targets of parochial altruism: attacks against groups that have more, or fewer, resources that the individual’s own group. We posit that these two types of parochial altruism result from two forms of inter-group comparison: envy and jealousy. The logics of envy predicts that individuals have a basic preference for targeting rich groups, and they actually follow this preference except when these groups have a high destructive capacity (meaning that the level of damages they can inflict is high). The logic of jealousy posits that individuals are more likely to target weaker outgroups when they get close to the ingroup level of resources, especially if they will pose a threat to the group in the future due to their increasing destructive capacity.

To test these hypotheses, our paper introduces a revised version of the Inter-group Prisoner Dilemma (IPD), a classic economic game in which individuals can engage in costly attacks against an outgroup to contribute to the welfare of their own group. We modified the standard game introducing multiple groups and inequality of resources between groups. The experiment took place in a laboratory in Grenoble, and mobilized 300 subjects.

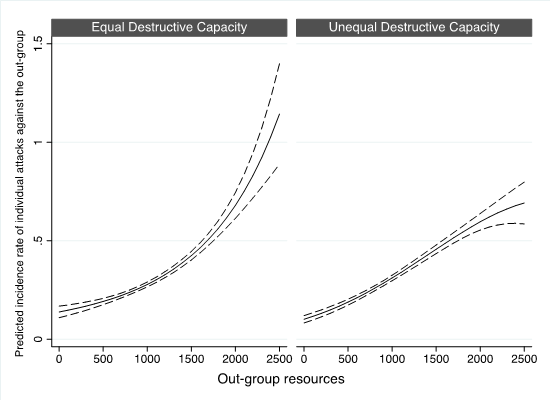

In line with our hypotheses, results show that individuals have a preference for targeting rich groups, but that attacks decrease when the inequality of destructiveness between groups is high. That is, individuals are less likely to attack the richest group if it has a higher capacity to retaliate and cause damages to the individual’s own group in return. Besides, individuals target weak outgroups when they are threatening their ingroup status, especially when the inequality of destructiveness between groups is high. Furthermore, as a clue of external validity of our experiment, we found that subjects on the left side of the political spectrum spent more money on attacking rich groups in our game, while individuals high in social dominance orientation spent more money on attacking poor groups.

In our game, we found that individuals have a basic preference for targeting rich groups. Yet, the attacks against the richest groups diminish once inequality in destructiveness is high. That is, individuals are less likely to attack the richest group if it has a higher capacity to retaliate and cause damages to the individual’s own group in return.

In a second step, we wanted to test the “real-world” implications of our experiment regarding the historical variations in the targets of terrorism. If we assume that the destructive capacity of economically dominant groups increases with their wealth in the real world, we should observe that political violence targeting dominant groups diminish in contexts of high inequality. Is this the case?

To investigate this, we tested the effect of economic inequality on right-wing and left-wing terrorist attacks in 24 countries from 1972 to 2016. The divide between left-wing and right-wing terrorism is a good proxy of the targeting of strong versus weak outgroups. Indeed, hostility toward strong groups is a key feature of left-wing ideologies, whose defining goal is to reduce inequalities. In contrast, right-wing terrorism consists in targeting groups which are not defined along economic divides, yet homeless people are common targets of right-wing terrorists. In line with our expectations, we found that the higher the level of economic inequality in a country the lower the number of left-wing terrorist attacks, while the level of inequality is not related to right-wing terrorist attacks.

Overall, our results suggest that contemporary high levels of inequality may lead to a right-wing orientation of political violence. Not through increasing right-wing violence, but through decreasing the share of left-wing violence targeting strong groups. We found that the asymmetric balance of power between the richest class and the majority, resulting from high material inequalities, deters individuals from struggling for equality. In contrast, under low inequalities, individuals become more willing to fight against the privileges of the richest class. This paradoxical effect is close to the observation from de Tocqueville that « the desire for equality always becomes more insatiable as equality is greater ».

Forthcoming in Political Behavior